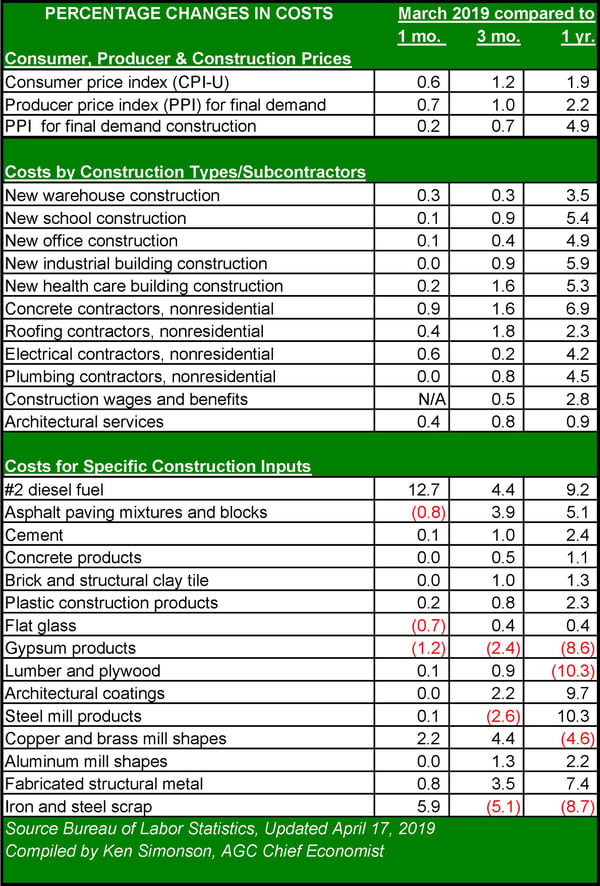

The government’s reading on producer prices over the past six months has eased worries that an extended inflationary cycle has begun. As of the March report on Producer Price Indexes (PPI) for construction and manufacturing, it appears that the mid-2018 spike was related to tariffs alone. Assuming that the upward pressure on construction inputs going forward should come from cyclical forces like pent-up wage growth or profits, construction pricing should more closely resemble the level of inflation in the overall economy.

Those individual materials that experienced significant year-over-year changes followed the prevailing trends in the industry. The stagnation of housing construction and residential investment, along with a buildup in supply, have put pressure on lumber and drywall prices, which fell 10.3 percent and 8.6 percent respectively. The early spring run up in oil prices translated into increases in #2 diesel fuel (9.2 percent) and asphalt products (8.2 percent). Year-over-year prices for steel and industrial metals were roughly ten percent higher but those prices have been falling since fall and are higher in comparison to 2018 prices that predated the implementation of tariffs on steel and aluminum. That year-over-year gap will disappear after May, as the long-term trend relating to over-supply drives pricing.

Inflation pressures overall are coming from two related sources. First is the upward pressure on wages and profits as the tight labor markets create supply constraints on contractors. The second source of inflationary pressure is from flat or declining productivity. Late in a business cycle, with unemployment at record low levels, there will be little opportunity for productivity gains except through technology improvements. Economists see these factors, along with the declining impact of central bank fiscal stimulus and global expansion, as a recipe for higher inflation.

“We now stand at an important point,” writes Ryan Severino, chief economist for JLL. “[T]he Fed sits on hold, wage growth is still accelerating, productivity growth will likely decelerate in 2019, and the blowback against globalization is causing some of the integration of the last few decades to reverse.”

March’s reading on inflation showed that inputs to construction were increasing at a rate that was only slightly higher than overall producer price inflation. The producer price index (PPI) for inputs to construction rose 2.7 percent year-over-year in March. One trend worth watching closely is the volatility in fuel prices. Along with the decline in steel and basic metals prices, the ten percent decline in fuel prices since mid 2018 has been a major factor in construction input price stabilization. Since the data was collected for February, however, prices for oil and energy overall have climbed higher, which could put prices for #2 diesel fuel, asphalt, roofing and other oil-related materials back to 2018 levels if the trend holds. The long-term trend for oil prices is for a return to higher prices – likely peaking well above $100 per barrel – before breaking downward by 2021 into a much longer cycle of low prices.

An increase in oil-related inputs would push construction inflation slightly higher, but more stable trade conditions and labor rates should offset the upward pressure. U.S. tariffs – or the threat of them – were the primary driver of mid-2018 price spikes. Assuming that trade deals with China, Europe and the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement are finalized (or that no further tariffs are imposed), construction inflation should primarily come from higher wages, productivity declines, and lower competitive pressures on contractors for the balance of 2019.

Share